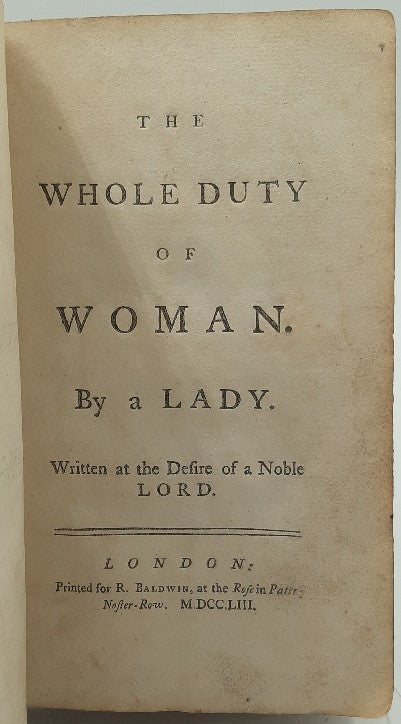

The Whole Duty of Woman. By a lady.

[KENRICK, William]

London: Printed for R. Baldwin, at the Rose in Pater-Noster-Row. 1753.

First edition. 8vo, 170x105mm. pp. xiv, [2], 88. Quarter calf, original paper covered boards, rubbing and wear to edges and corners with much of the paper covering worn. Rebacked, red morocco label, lettered in gilt. Foxing and browning and some ink marks, small tear to corner of E4 with no loss of text. Front pastedown has the ownership inscription of "Mrs Anne Cave, Barking Alley, 1761" and, opposite, on the recto of the front endpaper is inscribed "Elisbeath (sic) Castell, I.D".

William Kenrick was a literary chancer. In 1751, Robert Dodsley had published, with great success, The Oeconomy of Human Life, a collection of short essays on correct moral and social behaviour, purportedly written by a Chinese philosopher. Kenrick, spotting an appetite for moral guidance, wrote his own work, following Dodsley’s model of brief pieces with single word titles such as “Modesty”, “Reputation”, “Frugality” and “Education”. The title of Kenrick’s book is taken from a seventeenth-century work and he published The whole duty anonymously, pretending that it had been written by a woman. The central idea, that correct behaviour in a woman is more likely to arise when encouraged by another woman, allows Kenrick to hide behind a feminine mask while, all the time, praising the sort of characteristics that men expect women to display. This results in his treading a very fine line between irony and offensiveness. Consider the essay on “Curiosity”: “Seek not to know what is improper for thee; for happier is she who but knoweth a little, than she who is acquainted with too much”.

The Whole Duty of Woman was a great success, running to five editions during Kenrick’s life and remaining popular through the nineteenth century. However, it is hard to imagine a writer less appropriate than Kenrick to offer moral guidance. He has been described as “the black sheep of Grub Street” and he does seem to have been an entertainingly ghastly man. He published his New Dictionary of the English Language, heavily plagiarising Samuel Johnson’s. He libelled Oliver Goldsmith, he spread rumours about David Garrick’s homosexuality, he spent time in debtors’ prison, and he picked fights with almost everyone he came into contact with: “he was rarely without a public enemy” (ODNB). Indeed, Kenrick so thrived on disagreement that, if no-one rose to his provocations, he would, pseudonymously, write an intemperate response to his own argument in order to generate a controversy. In other words, just the sort of person to tell your wife, daughter or sister how to behave.